We agree – the Jetsons era has indeed arrived. Beyond the days of “smart” everything, now 3D printing has taken center stage in the tech world. While it is not so farfetched to imagine 3D-printed machine parts, prototype models, or even toys, it is might be harder to watch it printing foods, implantable medical devices, cosmetics, drugs and even human tissue. All too futuristic? Not really. The technology of 3D-print FDA-regulated products is, in large part, already here and rapidly progressing.

We agree – the Jetsons era has indeed arrived. Beyond the days of “smart” everything, now 3D printing has taken center stage in the tech world. While it is not so farfetched to imagine 3D-printed machine parts, prototype models, or even toys, it is might be harder to watch it printing foods, implantable medical devices, cosmetics, drugs and even human tissue. All too futuristic? Not really. The technology of 3D-print FDA-regulated products is, in large part, already here and rapidly progressing.

Yet, as technology continues to develop, questions arise as to whether, and how, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (“FDA”) regulatory framework will keep pace to impose the same safety, quality and efficacy standards to 3D-printed foods, drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices that currently apply to traditionally manufactured goods. How FDA chooses to deal with 3D-printed products will significantly impact not only barriers to market entry, but also post-marketing enforcement risks. Similarly, even assuming an FDA-regulated 3D-printed product is successfully brought to market in accordance with FDA standards, manufacturers must still assess options and potential challenges associated with protecting their intellectual property.

Through this multi-part blog series, we will explore these questions, considerations and challenges for 3D printing that are likely to be regulated by FDA, with particular focus on foods (consumed on earth and in space), cosmetics and medical devices. While, at this stage, FDA issues may raise more questions than clear answers, this blog series will explore and discuss the topics that are at the forefront of FDA’s agenda regarding 3D printing and, therefore, require careful consideration by any company that contemplates involvement in the 3D-printed foods, cosmetics or devices industries.

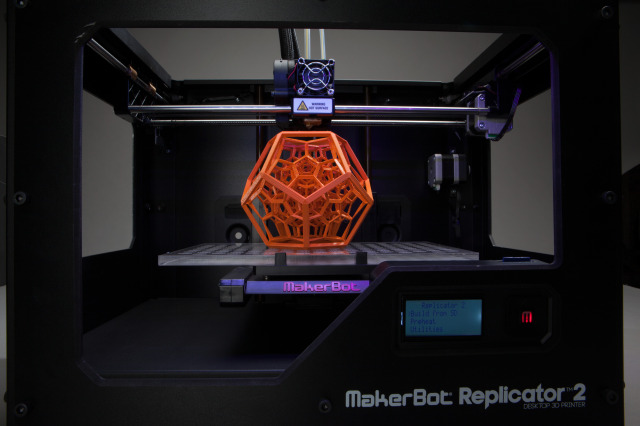

Overview of 3D Printing Technology: How Does One Print a Pizza, Palette or a Prosthetic?

3D printing, also referred to “additive manufacturing” or “rapid prototyping,” is the process of making three-dimensional objects from digital designs. Two of the most common types of printers are “disposition printers,” which deposit layers of materials until the 3D object is built, and “binding printers,” which build the object by binding, usually with adhesive or laser fusing, the underlying layers, to create a whole object at the end of the process. Perhaps this seems simplistic enough, but delving into the 3D printing of food highlights the multiple aspects of this process and underscores the potential challenges associated with fitting 3D-printed food into FDA’s current regulatory paradigm.

When it comes to printing food, the first step involves developing a computer-aided design (“CAD”) file, or animation modeling software, which tells the printer what to make and how to make it. After the finished design file is sent to the 3D printer, the user chooses a specific material. Depending on the printer and the end food product, the material may be food pastes, dry ingredients, raw ingredients to be cooked (dough, pasta, even raw scallops), or sugar-based materials (chocolates, candies). Additionally, the printer may require binding materials or a laser to “mold” the ingredients into the finished product. Binding materials might involve familiar media such as rubber, plastics, paper, polyurethane-like materials, metals and more.

In contrast to foods, 3D printed cosmetics are here and now—and will available for you to print at home. At least one company has developed a 3D printer intended for retail sale that would allow consumers to choose a color pigment then print that color into a blush, eye shadow, lip gloss or any other type of make-up. However, as with foods, there are FDA regulatory considerations that come into play. While many may not realize it, FDA also has authority over cosmetic products, and cosmetic ingredients. FDA can pursue enforcement action against cosmetics that are deemed “adulterated” (i.e., unsafe or unsanitary), or “misbranded” (i.e., the product’s labeling does not adhere to FDA regulatory requirements).

While cosmetic products and ingredients do not need FDA approval before going to market, with the exception of color additives, companies and individuals who manufacture or market cosmetics have a legal responsibility to ensure the safety of their products as well as compliance with FDA’s labeling regulations. If 3D cosmetic printers or printed cosmetics, become mainstream and available for home use, FDA and industry will have to give thought as to how to ensure that (1) the products’ ingredients (e.g., ink) safe and (2) the printing process does not cause the printed cosmetic to be contaminated, unsafe, or otherwise deemed “adulterated” by FDA. Further, to the extent that the printed cosmetic is made available for sale, there is a question as to how FDA’s cosmetic labeling requirements will apply to 3D printed cosmetics.

3D printing of medical devices takes the process yet a step further and allows for a high degree of customization. Think of 3D-produced dental implants which fit perfectly the first time because they are manufactured for your mouth. Or a map of a highly delicate cardiovascular procedure sized precisely to your size and needs, or more importantly, those of your newborn.

The applications are limited only by the medical profession’s imagination and requirements. Developing medical devices that allow for customization dovetails with FDA’s increased focus on promoting “personalized medicine.” As stated by FDA, “personalized medicine (also known as precision medicine) may be thought of as the tailoring of medical treatment to the individual characteristics, needs and preferences of a patient during all stages of care.”

Given FDA’s interested in product development geared toward personalized medicine, it is not surprising that 3D-printed medical devices have caught its attention, and we can expect further activity by the regulators in this arena.

As 3D printing enters the manufacture of foods, cosmetics and medical devices in full force, the FDA will develop policies and protocols to address these applications.