The long running saga of the FTC versus POM Wonderful took a major turn today as the D.C. Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part the FTC’s Order that POM had made deceptive claims about its pomegranate juice products. In 2010, the FTC sued POM alleging it had made false and unsubstantiated claims about the ability of its product to prevent or ameliorate heart disease, prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction. After an extended trial, the FTC’s Administrative Law Judge largely found for the FTC (not a huge surprise). The FTC Commissioners largely affirmed that decision (another shocker). However, Commissioner Ohlhausen, in what would turn out to be an ominous foreshadowing for the Commission as a whole (jump to the end of the blog if you can’t stand the suspense), and who wrote the Commission’s opinion, disagreed with the majority’s view that two Randomly Controlled Clinical Trials (RCTs) should be required as part of the order. POM appealed to the DC Circuit challenging the factual and legal bases on which the FTC relied as well as the remedy imposed. The DC Circuit affirmed on liability, but modified that part of the FTC’s order that required POM to have two RCTs to substantiate any disease claims going forward. The revised order will require only one RCT for any disease claims.

The long running saga of the FTC versus POM Wonderful took a major turn today as the D.C. Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part the FTC’s Order that POM had made deceptive claims about its pomegranate juice products. In 2010, the FTC sued POM alleging it had made false and unsubstantiated claims about the ability of its product to prevent or ameliorate heart disease, prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction. After an extended trial, the FTC’s Administrative Law Judge largely found for the FTC (not a huge surprise). The FTC Commissioners largely affirmed that decision (another shocker). However, Commissioner Ohlhausen, in what would turn out to be an ominous foreshadowing for the Commission as a whole (jump to the end of the blog if you can’t stand the suspense), and who wrote the Commission’s opinion, disagreed with the majority’s view that two Randomly Controlled Clinical Trials (RCTs) should be required as part of the order. POM appealed to the DC Circuit challenging the factual and legal bases on which the FTC relied as well as the remedy imposed. The DC Circuit affirmed on liability, but modified that part of the FTC’s order that required POM to have two RCTs to substantiate any disease claims going forward. The revised order will require only one RCT for any disease claims.

The DC Circuit found that there was no basis for setting aside the FTC’s finding of what efficacy and establishment claims POM had made in its advertising, noting the careful record the ALJ had made and the thorough treatment the Commission had given the issues in its opinion. The DC Circuit agreed with the FTC that the use of words such as “promising,” or “initial” to describe certain studies referenced in POM’s advertising failed to adequately qualify the ad so that an establishment claim was not made. Regarding the level of substantiation necessary, the court noted the FTC’s special expertise in this area. The court noted that its role was not to independently weigh the evidence but to determine whether there was substantial evidence to support the FTC’s findings. The court decided there was. The FTC had found that RCTs were necessary to substantiate the disease claims made. The court found adequate evidence to support that finding noting that the controlled, random and double blind aspects of an RCT all serve important functions in evaluating the efficacy of a product or treatment. POM argued that applying the RCT standard to food products was too onerous and expensive. The court agreed with the FTC that although there might be certain instances where it was not possible to conduct double-blind studies of food products, this was not such a situation. Among other things, the court pointed to the fact that POM had done some RCTs on its products. Regarding cost, the court displayed no sympathy for the marketer’s plight finding that if the claim was too expensive to substantiate then the claim should not be made. Significantly, the court noted that marketers could make lesser health claims without an RCT including claims that accurately reflect the type and results of the science supporting a claim.Continue Reading The Saga of the Forbidden Fruit Part III

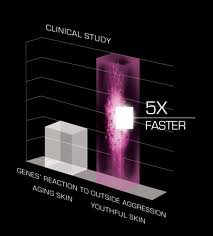

Who doesn’t want young-acting skin? We’re not talking about the way skin acted in the zits-on-picture-day years, but rather the dewy glow of innocence – the Code of Youth.

Who doesn’t want young-acting skin? We’re not talking about the way skin acted in the zits-on-picture-day years, but rather the dewy glow of innocence – the Code of Youth. Building buzz around your product is usually a good thing. But creating a product out of buzz not necessarily so. Vibram USA Inc., a company promoting their

Building buzz around your product is usually a good thing. But creating a product out of buzz not necessarily so. Vibram USA Inc., a company promoting their